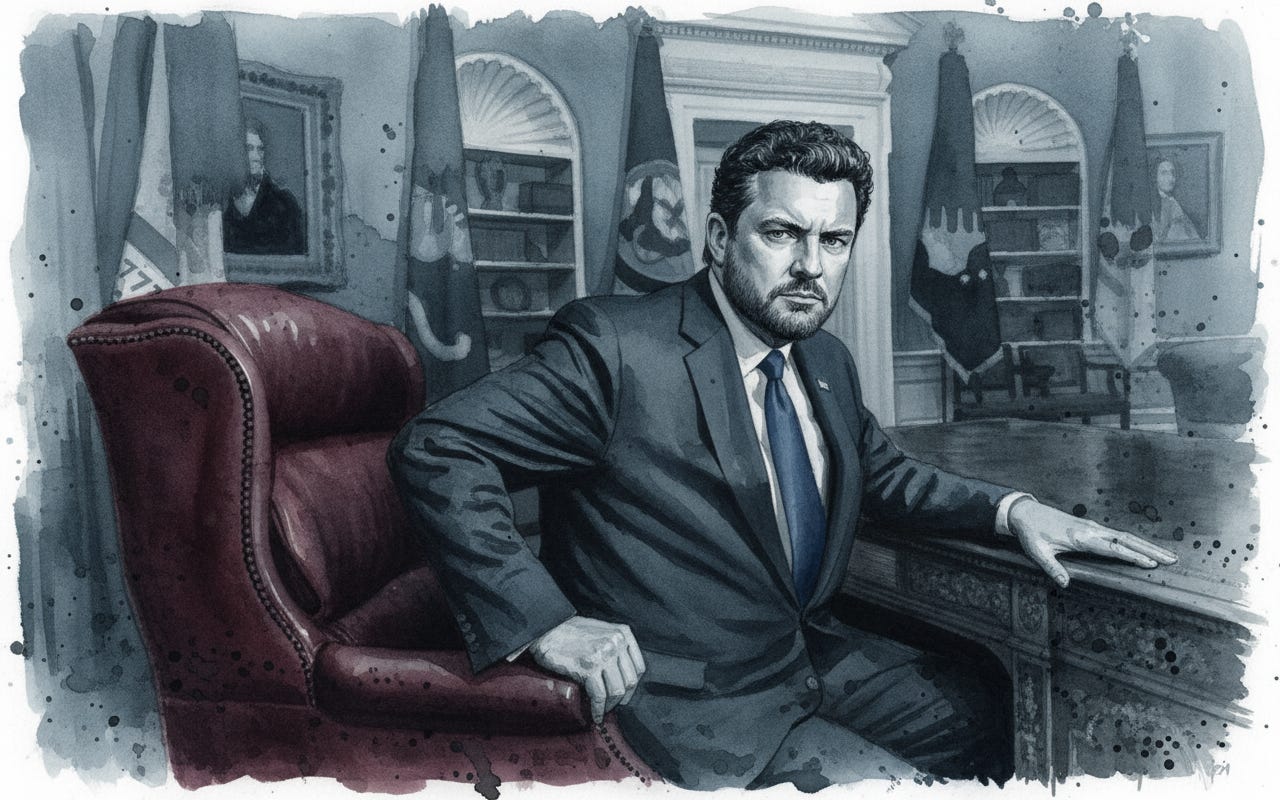

Malignant: No One

They keep talking. I’m watching their mouth move, waiting for the pause, the breath, the moment when I can jump in with something better, something about me, something that matters.

Prologue:

This story shares a universe with others in this collection:

2 of 4: Malignant: No One, (1981) Age 21 (Next)

3 of 4: Malignant: No One, (1962), Age 20 Months

4 of 4: Malignant: No One and Adam, 2025

Age 65

2025: The Mirror

The reflection is perfect. Always has been. Best anyone’s ever seen. I know this the way I know my own name, the way I know the sun comes up. It’s just fact. I look just as good at 65 as I did at 45, no 35.

I’m adjusting my collar when someone walks past behind me. They glance, look away. Why did they look away? That’s the question. Are they intimidated? Probably. People usually are. Or maybe they’re jealous (definitely jealous) of what they see.

I smile at myself. The smile is good. Strong. I’ve practiced this smile though I don’t remember practicing. It’s just always been there, always been this good.

“Looking sharp,” I say out loud to no one. The sound of my voice fills the space perfectly.

2025: The Numbers

The phone screen glows. 836 new followers. Should be 8,360. Should be 83,600. Someone isn’t doing their job.

I scroll through comments. Skip the good ones (boring, expected), stop at criticism. Some nobody, some nothing, saying I’m wrong about something. The heat starts in my chest. My thumb hovers over reply.

“You clearly don’t understand,” I type. Delete it. “Actually, if you knew anything,” I type. Delete that too. What I finally send is longer, more detailed, explaining exactly why they’re stupid, why I’m right, why everyone agrees with me.

I don’t wait for a response. Don’t need to. I already know what it’ll say: nothing, because I destroyed them, or something pathetic, which proves I destroyed them.

Either way, I won.

2025: The Breakfast Table

Someone is talking. I’m nodding. The words are just sounds, like rain on windows, background noise while I think about what I’ll say next.

“That’s interesting,” I say, though I didn’t hear what they said. This is a good response. People like when you say things are interesting.

They keep talking. I’m watching their mouth move, waiting for the pause, the breath, the moment when I can jump in with something better, something about me, something that matters.

“You know what happened to me yesterday?” I don’t wait for them to say yes. Why would I? The story is already coming out, already good, already getting better as I tell it.

I wasn’t planning to exaggerate, but the exaggeration makes it work, makes their eyes widen, makes the story worth telling.

They laugh when I want them to laugh. This is how conversation works. I say things, they respond correctly, everyone wins.

Interstitial: “Malignant” is broken into different sub-parts and side-stories that explore the themes and characters at different times and through different points of view. Continue reading in linear time, or explore more of the backstory, Malignant, Age 21 (1981), and then return to read the rest.

2025: Michael

I’m holding the report. My hands are actually shaking. Not from cold, from something else, something I don’t want to name.

He’s going to hate this. The numbers are down. Not by much, but enough. Enough that they matter. Enough that he’ll blame someone. I don’t know why he gets so upset. He’ll just lie about them anyway. He says whatever he wants in the moment and he even contradicts himself moments later. And no one corrects him. He barely reads the reports anyway. Never wants the facts, the details. “Are the numbers good”? I’m afraid to answer. The analysts twist themselves in knots and then knots trying to make sense of the difference between the facts, and his facts. A thankless, impossible job. A job that can get you some visibility, but kill your career if it sticks. Some make enough to weather the consequences. Some try to reinvent themselves.

No one gets out of here without some scars.

I rehearsed this. Three times. In the car, in the bathroom, standing outside his door. “The quarterly results show.” No, that’s too formal. “We need to discuss.” No, that sounds like I’m in charge. I’m not in charge. I’m never in charge. If I told him that the numbers were good, he’d never know. But on the oft chance that someone has the courage to challenge him, I’d be fucked.

His assistants are good about protecting him with yes men and women. And when someone slips through with more ethics or courage, he lets them know.

I knock. He doesn’t say come in. He just starts talking, mid-sentence, like I’ve been here the whole time, like I’m supposed to know what he’s talking about.

I nod. I always nod. “So you understand,” he says. I don’t understand. But I nod again.

“The report,” I manage. He takes it without looking. Glances at the first page. The second. His face doesn’t change but the air does. Everything gets tight.

“Who did this?” I did this. I’m holding my breath. “The team,” I say. “We all—” “Who approved these numbers?” His voice hasn’t gotten louder but it feels louder. “They’re accurate, I checked,” “Then you checked wrong.”

He’s not yelling. That’s worse. The quietness is worse. I’d prefer yelling. Yelling ends. This just keeps going, his eyes on me, his silence saying everything his mouth doesn’t have to. 5 minutes from now, he’ll be on to the next train of thought, the next conversation. I won’t even exist until I need to exist again. I’m grateful for that.

Age 13

1973: The Discovery

The woods behind the house are mine. Not really. But mine in the way that matters; where I know every trail, every clearing, every place where the trees grow too thick for adults to follow.

I’m walking with a stick. Found it by the creek. It’s perfect. Straight. Heavy. Good weight. I swing it at nothing, at air, a sword at the heads of invisible enemies.

There’s a bird. Small one. Brown. It’s hopping around near a log, doing whatever birds do. Being stupid probably. Being weak. I stop walking. The bird doesn’t notice me. Doesn’t see me standing here. That’s its first mistake.

I move closer. Slow. Each step careful. The bird is focused on the ground, pecking at something, completely unaware. Completely vulnerable. This is what happens when you’re not paying attention. This is what you get for being oblivious.

The stick comes down fast. Not hard enough to kill it immediately. Just hard enough to break something. The bird makes a sound. High-pitched. Panicked. Its wing is bent wrong.

I crouch down, watching it. The bird tries to fly but can’t. One wing works, one doesn’t. It flops around in the leaves, making that sound, that desperate chirping that means it knows something is wrong but doesn’t understand what.

The bird stops flopping. Just sits there, breathing fast, looking at me with those small black eyes. It knows. Knows I did this. Knows I’m the reason it can’t fly anymore.

I pick up the stick again. This time I bring it down harder. The sound stops. The bird is still. And that feeling in my chest, that warmth, it’s fading. But for a moment, for those few seconds when the bird was hurt but not dead, when it was suffering and knew I caused it, I felt something. Felt real. Felt present. Felt alive.

I walk away, leaving the bird there. Leaving the stick. My hands are shaking slightly. Not from guilt. From something else. From the aftershock of that feeling, that brief moment of mattering.

I picture the bird being devoured by ants its eyes, empty holes. Skeletal remains decorated by a few remaining feathers. When I return it doesn’t look the way I had pictured or hoped that it would. There was little left of it. I imagined that soon weather and insects and other animals that feast on the scraps of carrion would reduce it to nothing but dust. There would be nothing left to mark my passing - my existence.

At dinner, Mother is talking. Father is silent. He rarely speaks to me. I am distracted by a daydream, a spell where I try to cast a memory of his voice. When he does speak to me, he refers to me as “boy,” never by my name. I wonder sometimes if he even knows my name. My older brother is there. My sister. Everyone arranged around the table like we’re normal. Like we’re a family.

When you are part of a family, it means that you’re someone important.

“How was school?” Mother asks, but she’s not looking at me. She’s looking at my brother.

“Fine,” he says. “Got an A on my math test.”

“That’s wonderful.” Mother smiles. Father nods. Everyone glows with approval. My brother is basking in it, soaking it up like sunlight.

“I did something interesting today,” I say. Nobody looks up. “I found a bird.”

“That’s nice,” Mother says absently. She’s still focused on my brother. “Tell me more about the test.”

I’m invisible. Sitting right here at the table and nobody sees me. Nobody cares. That feeling from earlier, that warm alive feeling, it’s completely gone. I’m hollow again. Empty. A shape that takes up space but doesn’t matter.

“May I be excused?” I ask.

“You haven’t finished your dinner,” Mother says, but she still isn’t looking at me.

“I’m not hungry.”

“You’re never hungry. You’re too picky. It’s exhausting.” Her voice has an edge now. Sharp. Annoyed. Finally I exist to her, but only as a problem. Only as something requiring energy she doesn’t want to spend.

“Just let him go,” Father says. His first words of the meal. Not defending me. Just dismissing me. Wanting me gone so the real family, the good children, can continue their dinner in peace.

I’m in my room. Door closed. Lying on the bed staring at the ceiling. There’s a crack up there. Small. Branching. I’ve traced it a thousand times. Know every line. Every deviation.

Tomorrow is school. There’s a kid in my class. Daniel. He’s smaller than me. Weaker. He cries sometimes when the teacher calls on him and he doesn’t know the answer. Everyone thinks he’s pathetic. I think he’s pathetic too.

But he’s also useful. Because when I push him in the hall, when I say something that makes his face crumple, something happens. That feeling comes back. That warm alive feeling. Like I’m real. Like I exist. Like I’m here and undeniable and powerful.

I’m not thinking about right or wrong. Those words don’t mean anything. They’re just sounds people make to control you, to keep you small, to stop you from taking what you need.

And what I need is to feel something. What I need is proof that I’m here. What I need is someone else’s pain to mirror back to me that I exist, I matter, I am.

Mother comes in without knocking. She never knocks. Why would she? Privacy is for people whose inner lives interest other people.

“You need to try harder,” she says. No preamble. No warmth.

“At what?”

“At everything. Your teachers say you’re difficult. You don’t pay attention. You don’t make friends.”

“I have friends.”

“No, you don’t.” She says it flatly. Statement of fact. “You have children who tolerate you because they’re polite. That’s not friendship.”

The words should hurt. Probably she wants them to hurt. But they don’t because she’s right. And because I don’t care. What I care about is how easily she says it. How little effort it takes for her to confirm what I already know: that I’m defective. Wrong. Not like the others.

“Your brother was never like this,” she continues. “Neither was your sister. I don’t understand what’s wrong with you.”

There it is. The question she’s been asking my whole life. What’s wrong with you? As if I’m broken. As if I came out wrong. As if she’d send me back if she could.

For a moment I consider, “am I broken?” But I am learning to deny these thoughts, these beliefs that I bury over and over and over again and replace them with reflections from the world around me - their reactions and responses.

They prove that “maybe nothing’s wrong with me. Maybe something’s wrong with her or wrong with everyone else?”

She makes a sound. Harsh. Dismissive. “That’s exactly the kind of thinking that’s holding you back. This attitude. This...” She waves her hand at me, at all of me, like I’m something distasteful. “Fix it. Figure it out. I don’t have the energy for this.”

She leaves. Doesn’t close the door. I have to get up and close it myself.

I’m back on the bed. The ceiling crack is still there. Still branching. Still splitting. I’m thinking about the bird. About the moment before I hit it. About how peaceful it was, just pecking at the ground, not knowing I was there.

That’s everyone. That’s the whole world. Just pecking at the ground. Not paying attention. Not seeing me. Not understanding that I’m here, that I’m dangerous, that I can make them notice.

Tomorrow I’ll make Daniel notice. I’ll say something or do something that makes him hurt. And for a moment, for those beautiful few seconds, I’ll feel real. I’ll feel alive. I’ll feel like I matter.

And then it’ll fade. And I’ll need to do it again. And again. And again.

Because this is who I am. This is what I need. This is the only way I know how to exist.

1973: The Witness

My golden retriever’s name is Copper. He’s four years old and perfect and completely good in the way only dogs can be. He trusts everyone. Loves everyone. Thinks the whole world wants to be his friend.

We’re at the Whitmore house. My parents are friends with his parents. Old friends. The kind who play tennis together and go to the same charity events and have standing dinner reservations at the club.

I didn’t want to come. I told my mother that. But she said, “It’s important to maintain relationships” and “The Whitmores are good people” and “You’ll have fun with their son. He’s your age.”

He’s not my age, not really. He’s 13 like me, but there’s something different about him. Something I noticed the first time we met. Something that made my skin prickle with warning.

We’re in their backyard. Enormous. Manicured. Pool. Tennis court. Everything. Copper is running around, ecstatic with all this space, this grass, this freedom.

The boy (I can’t bring myself to think of him by name) is sitting on the patio. Watching. Not reading or playing or doing anything. Just watching.

“Your dog is pretty hyper,” he says.

“He’s happy. He likes running.”

“Running is stupid. What a stupid dog.”

I don’t respond. I’ve learned not to respond. Anything I say, he twists. Makes wrong. Makes sound dumb. So I just watch Copper, focus on him, on his joy, on his simple goodness.

“Come here, dog,” the boy calls. I say, “his name is Copper.” Sweet trusting Copper, runs over immediately. Tail wagging. Mouth open in that dog smile.

The boy reaches down like he’s going to pet him. Copper leans in, accepting the affection, expecting love because that’s all he knows.

And then the boy’s foot comes up. Fast. Hard. Right into Copper’s ribs.

The yelp is high-pitched. Shocked. Copper stumbles back, looking confused. Looking at the boy like he must have made a mistake. Like surely this human didn’t mean to hurt him.

“Why did you do that?” I’m running over. Kneeling by Copper. Checking him. His tail is down. He’s shaking. His bladder empties.

“Do what?” The boy’s voice is flat. Innocent.

“You kicked him. You kicked my dog.”

“I didn’t kick him. I moved him. He was in my space.”

“He wasn’t in your space. You called him over.”

The boy shrugs. “Maybe he shouldn’t be so annoying.”

I’m looking at him. Really looking. And what I see makes my stomach drop. His face is blank. Completely blank. No guilt. No remorse. No recognition that he hurt something, that Copper is in pain, that what he did was cruel.

“Stay away from my dog.” My voice is shaking. Copper is pressed against my leg, still shaking too.

“It’s my yard. Maybe you should keep better control of your dog.”

2025: The Meeting

They’re all here. Good. This is important. What’s important? I’ll figure that out while I’m talking. That’s how I work best, in the moment, spontaneous, brilliant under pressure.

When my father died, nearly twenty years ago, I took over the company that he started. I had an office on the floor below his, and then I took over as CEO. The big office with glass windows that look over the beautiful girls. The VPs were all men, but the directors, all women. Every one of them fuckable.

I would helm the big ideas, the interviews, the PR events. I go to the SuperBowls and the celebrity events. I’m the CEO now and I get the credit. But I left all of the loyal soldiers in place. The peons who dealt with the lawyers, the accountants, marketing product development.

“Let’s begin,” I say. They go around the table and celebrate what we’re creating under my leadership. Once around, and someone starts presenting. Slides. So many slides. Why do people need slides? Just talk. Just be interesting like I am.

I interrupt at slide three. “That’s not going to work.” They pause. Good. “What I mean is,” they start. “I know what you mean. What I’m saying is, that won’t work.”

I don’t actually know if it’ll work or not. But saying it won’t puts me in control, makes them explain things to me, makes everyone look at me instead of the slides.

“What would you suggest?” they ask. This is a trap. Obviously. They want me to commit to something so they can blame me later when it fails.

“I suggest,” I say slowly, buying time, “that we think bigger. Bolder. That’s always been my strength, bold thinking.”

Some people nod. The smart ones. The ones who understand how this works.

2025: Sarah

I’m eating a salad I don’t taste. He’s across from me, talking about something, something he did, something amazing, I stopped listening three minutes ago but my face hasn’t changed. He talks while he eats. So much talking. He never, ever stops fucking talking. I notice the salad that he accidentally spit on the table and I want to look, but I won’t. I can’t. He didn’t notice and if I draw attention to it, he’ll punish me for embarrassing him.

I’ve learned to do this: maintain the expression, the slight smile, the occasional nod, while my mind goes somewhere else, anywhere else. When I met him for lunch today, I pretended to see a friend and turned my head when he tried to kiss me on the mouth. I know it’s a form of dominance. Today, my cheek was the part of my body sacrificed to his lips.

“Don’t you think?” he says. I don’t know what I’m supposed to think. “Absolutely,” I say. This works ninety percent of the time.

He keeps talking. He talks about stupid things. Just talk. I notice his hands. They move constantly, conducting an invisible orchestra, pointing, gesturing, claiming space that isn’t his. He says that I’m pretty, but he uses words like “gorgeous” and comments on my lips and my hips. His eyes undress me and break his concentration by looking away. I’ve trained myself to reach for my phone or to drop my fork, anything to change the focus.

My phone buzzes. I glance down. “Are you listening?” he says. The temperature drops. “Of course, I just.” “You just what? You just decided your phone is more important than what I’m saying?”

I wasn’t listening. He’s right about that. But he’s right in that way that makes me feel small, that makes the room shrink, that makes me wish I’d never sat down.

“I’m sorry,” I say. I’m always sorry. Even when I’m not.

2025: Afternoon

There’s a problem. Someone is telling me about a problem. I’m not interested in problems. Problems are for other people. Why the fuck are they bringing their problems to me?

“Fix it,” I say. “But we need your approval.” “You have it. Fixed. Done.” I wave my hand. Problem solved. That’s leadership.

They’re still standing there. Why are they still standing there? “Was there something else?” My voice has an edge now. The edge works. They leave.

The office is quiet. Too quiet. I open my phone, scroll through photos of myself. This one’s good. That one’s better. I post the better one with a caption about excellence, about never settling, about being the best.

Three likes in thirty seconds. Not enough. Where is everyone? Why aren’t they seeing this?

2025: The Confrontation

Someone disagrees with me. In front of everyone. Actually says, “I don’t think that’s right.”

The room goes still. I can feel them all watching, waiting to see what I’ll do.

I smile. “You don’t think that’s right.” I’m repeating their words back slowly, like I’m examining them, like they’re interesting specimens.

“Based on what?” I ask. They start explaining. I’m not listening to the explanation. I’m looking for the weakness, the soft spot, the place where I can push.

There. There it is. They said “I think” twice. They’re uncertain. They’re guessing.

“You think,” I say. “That’s the problem here. You think, but you don’t know. I know. There’s a difference.”

Their face changes. Just slightly. Just enough. That’s what I wanted. That moment of doubt, of wondering if maybe they’re wrong, if maybe I’m right, if maybe they should’ve just kept quiet.

They should’ve kept quiet.

2025: Janet

I’m in the kitchen when he comes home. I hear the door, hear his footsteps, hear the particular way he drops his things that means he’s in a mood.

“Long day?” I ask. Neutral. Always neutral. “They’re all long when you’re surrounded by incompetence.”

I’m stirring something. What am I stirring? It doesn’t matter. The stirring gives me something to look at besides him.

“Dinner’s almost ready.” “I’m not hungry.” He is hungry. He’s always hungry. But if I made his favorite, he’s not hungry. If I made something else, why didn’t I make his favorite?

I’ve learned there’s no winning. There’s only damage control.

“How was your day?” he asks. This is new. He never asks. I’m suspicious immediately. “Fine. Just the usual.” “That’s nice.”

He’s not listening. He’s on his phone, scrolling, frowning, the light reflecting in his eyes like small cold fires.

2025: Night

The TV is on. I’m watching something, something about someone less successful than me. Makes me feel good. Makes me feel right about my choices, about my life, about everything.

Someone on screen is crying about something. Weak. That’s weak. I’ve never cried. Don’t remember ever crying. Crying is for people who haven’t figured out how to be strong like I am.

My phone buzzes. A message. Finally. Someone agreeing with something I said earlier. “You’re so right,” they wrote. Three words. Perfect words. The best words anyone’s ever written to me.

I screenshot it. Might post it later. Might need it as proof when someone inevitably tries to say I was wrong.

I’m not wrong. I’m never wrong. That’s just facts.

2025: Before Sleep

The bedroom is dark. Someone is already in bed, already pretending to sleep. I know they’re pretending. No one falls asleep that fast.

I get in without speaking. What would I say? What is there to say?

My phone glows one more time. One more check. Numbers. Always numbers. Never enough. Tomorrow they’ll be bigger. They have to be bigger. I’ll make sure they’re bigger. Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night with a big idea and I start calling people. If no one answers, they’re on the list, but I pick the people who will answer and listen. This is what’s necessary when you run a big company.

I’ll post something brilliant. I’ll say something people can’t ignore. I’ll remind everyone who I am, what I am, why I matter.

20 Months

1962: The Mother

The crying starts again. Always the crying with this one.

I check the clock on the mantle. Twenty minutes since the last time. Twenty minutes of blessed quiet, and now it begins again. The sound scrapes against my nerves like fingernails on silk.

Margaret is reading in the sunroom. Perfect child, that one. Always has been. Thomas plays with his blocks, building towers and knocking them down, laughing at the destruction. Normal. These are normal children who understand their place in the world.

But this one.

The wailing intensifies. I can picture him in there, red-faced and demanding. Always demanding. As if the world owes him something simply for existing.

“Let him cry it out,” Mother said when she visited last month. “You’re making him soft with all that coddling.” But I don’t coddle. I barely touch him anymore. Something about his neediness repulses me, the way he grabs and clutches, the way his eyes follow me with that desperate hunger.

The other two were never like this. They cried when hungry, when wet, when tired. Simple needs with simple solutions. This one cries for attention. Pure attention. I can tell the difference now, the manipulative edge to it, the way it rises and falls like he’s testing which pitch will bring someone running.

I climb the stairs. Each step feels heavier than the last.

“Enough!” The word comes out sharper than intended. The crying stops for a moment, then starts again louder. Always louder. It’s like he feeds on the reaction, any reaction, even anger.

“You’re fine,” I tell him. “You’re fed. You’re dry. You’re fine.”

But he’s not fine. Something in those eyes tells me he’ll never be fine. They don’t look at me the way Margaret’s did at this age, with love and trust. They look at me like I’m a puzzle to solve, a lock to pick.

Charles won’t even hold him anymore. “Something off about that one,” he said last week, handing the baby back to Martha after less than a minute. “Gives me the shivers.” Charles, who never notices anything, noticed that.

The crying transforms into a different sound. A kind of growl. He’s gripping the crib rails, shaking them. Testing their strength. Testing mine.

I turn and walk away. Let him exhaust himself. That’s what the books say. Don’t reward the behavior.

But the sound follows me down the hall, down the stairs, into every corner of this house. It’s not just crying anymore. It’s something else. Something that makes my skin crawl in ways I can’t explain to the other mothers at the club, the ones who coo over their babies and talk about their little angels.

This is no angel.

Margaret looks up from her book as I pass. “Is the baby alright, Mother?”

The baby. We still call him that. Twenty months old and we still call him “the baby” like we’re afraid to make him more real by using his name. Like naming him will cement him into our lives in ways we can’t take back.

“He’s fine,” I say, the lie bitter on my tongue.

Through the window, I see the Pemberton children playing in their garden. Normal children doing normal things. Their mother waves. I wave back, a pantomime of suburban pleasantness while that sound continues upstairs.

I pour myself a gin. Too early, but the edges need softening. The doctor says it’s just a phase, that some children are more difficult than others. But he doesn’t see what I see. Doesn’t feel what I feel when I’m alone with him.

The crying stops. Abrupt silence. This is worse somehow. The quiet means he’s planning something, working out his next move. Even at twenty months, he’s always calculating.

I should check on him. Any normal mother would check.

Instead, I pour another gin and watch the Pemberton children chase butterflies in the afternoon sun, trying to remember what it felt like to love something that simple.

2025: The Dream

I’m in a room full of people applauding. They’re all looking at me. This is how it should be. This is how it always is in my head.

Someone is giving a speech about me, about my achievements, about my genius. The words are exactly right. How do they know the exact right words? Because they’re true. Because everyone knows them.

I’m walking to a stage. The lights are bright. I’m waving. They’re cheering louder. This is real. This has to be real. This is the only thing that’s ever been real.

I open my mouth to speak, to say something profound, something they’ll quote forever, but before the words come...

Morning light. Ceiling. The same ceiling as yesterday. The same ceiling as tomorrow. The dream fades but the feeling stays: that somewhere, somehow, everyone understands what I’ve always known.

Time to start again.

Epilogue

A Note on Interconnection:

Some of the characters and themes in my stories intersect. They exist in the same world, shaped and governed by the same rules and forces. Read them in any order. The themes echo regardless of sequence.

Interconnections:

2 of 4: Malignant: No One, (1981) Age 21 (Next)

3 of 4: Malignant: No One, (1962), Age 20 Months

4 of 4: Malignant: No One and Adam, 2025